You’re traveling through the dark dry forests of Madagascar, an island off the southeast coast of Africa. You hear a rustling sound in the trees to the left. You peer through the leaves, but see only shade and mist. Slowly, out of the fog, orange reflective eyes appear. You hear a ghostly cry! You feel frightened. Is it a ghost? No! It’s a Lemur!

Lemurs can sound spooky in nature. Even their name is derived from the Latin word “lemures” which means “ghosts” or “nocturnal spirits.” The Malagasy people of native Madagascar believed that lemurs were phantoms of departed souls, haunters of the night.

If you’ve visited the Louisville Zoo’s lemurs, you already know lemurs aren’t spooky at all! These furry little phantoms are actually cute and playful. The Louisville Zoo has four lemurs: three ring-tailed lemurs and one of the black and white ruffed variety. Native to the hot climates of Madagascar, most lemurs enjoy sunbathing; you can often see them relaxing together in a group facing the sun in what resembles yoga positions.

Sam Clites is the lead zookeeper for our lemurs. He has been with the Louisville Zoo since the early 1980’s when he started working here as a volunteer. Since becoming a zookeeper, Clites has worked with the lemurs and other primates in the lemur exhibit off and on for more than 20 years.

Sam Clites is the lead zookeeper for our lemurs. He has been with the Louisville Zoo since the early 1980’s when he started working here as a volunteer. Since becoming a zookeeper, Clites has worked with the lemurs and other primates in the lemur exhibit off and on for more than 20 years.

With four active lemurs to look after, you can imagine keepers have a lot to do! What might a typical day look like for a lemur keeper and his charges?

“When I come in the morning,” says Clites. “I first make sure Bruce has taken his supplement to help his liver function.” Bruce, our ruffed lemur, is the most senior lemur at age 24. You can recognize him by his coloring — strongly constrasting in black and white. “Night keepers medicate Bruce before we get here, but we have to make sure he has taken his medicine.” Keepers try hiding the pills in approved food items like dates or bananas, but that doesn’t always work with Bruce — who is a very clever lemur!

After caring for Bruce, the keepers clean inside the exhibit to ready it for the day. Keepers also make the lemurs’ diets that consist of different fruits and vegetables, both fresh and dried. The lemurs get daily treats as well including raisins, dried cranberries and dried cherries.

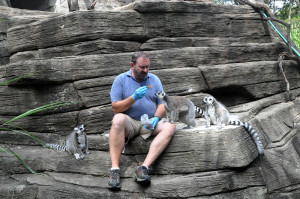

“We prefer to hand feed the ringtails much of their diet to ensure each gets the appropriate amount,” explains Clites. “Hand feeding also reinforces the building of a trust relationship between each lemur and keeper. We have to wait for Bruce because he takes a while to eat now — as he’s gotten older he forgets what he’s doing sometimes!” As many of you know, caring for geriatric animals takes patience, diligence and compassion.

In order to ensure proper food, medication and care, keepers are able to work personally with the geriatric lemurs through long-time training and relationship building. The lemurs are comfortable approaching the keepers for afternoon snacks, or (in the case of our three ring-tailed lemurs) taking the treat directly from the keeper.

“Paul and Faust vie for the most attention,” says Clites. “If you’re in the exhibit, they will approach and sit around you. Paul’s realized that if he can use cuteness to his advantage, he’ll get more treats. He likes to come up and stand on the foot of the person with the food and stare up at them to wait for a treat.”

Lemurs are known for being intelligent and very curious. “We have a small automotive mirror that we clip up in their bedrooms and sometimes catch them peeking in at themselves and vocalizing at the lemur they see in the mirror,” said Clites.

Though Keepers provide many enrichment items for the lemurs, usually what the lemurs enjoy most is being able to watch and interact with people.

Ring-tailed lemurs are classified as endangered, while ruffed lemurs are classified as critically endangered. “Lemurs are only found on the island of Madagascar,” explains Clites, “and their forest habitats are being converted into farmland or cut down for wood. As a result, the forests they love are quickly vanishing and with them, stable populations of lemurs. The animals have nowhere to go.”

Many lemur conservationists are working to engage the Madagascar community in conservation efforts to protect the lemurs and their threatened habitats: a strategy that conservation biologists are learning is necessary for any success over the long term.

“Conservation scientists are trying to work with Madagascar residents to remind them that they have something special that is worth protecting — something that’s not found anywhere else in the world,” Clites explained. “In some places, this collaboration is working and people are getting involved.” For example, the local residents manage the Anja Community Reserve in southern Madagascar and have formed an association to preserve wildlife like the forest’s large population of ring-tailed lemurs.

If you would like to know more about lemurs and how to help them, click here. Be sure to head to the Zoo to watch your favorite lemur friends in action. You might even try taking a quiet moment to join them in their sun worship and meditation session.